Eric's Epic Journey.

Eric Appleton is founder of Appletons tree nursery, based in Wai-iti, just south of Wakefield. He’s been on the job for over fifty years. It’s almost a certainty that you have enjoyed the shade cast by trees that started life at Appletons nursery, and an absolute certainty that you have filled your lungs with air containing oxygen released by Appleton trees.

Eric was born in 1934, in Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, a renowned centre for iron smelting, and the source of the steel used in countless buildings and structures throughout the world, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Pre-war, the word ‘pollution’ wasn’t a part of most people’s vocabulary, much less an issue to be addressed. Throughout his childhood, the air that he breathed, would have often been contaminated in excess of current WHO guidelines.

But in every respect, he seems to be much younger than his ninety-one years. If we were all similarly blessed, the superannuation age could be raised by fifteen years, and the government would have plenty of money to fund health and education. Eric has obviously inherited a set of genes which are giving him an extended ‘best before’ date, but he has also helped himself by pursuing a life’s work that has provided endless interest.

Despite having a stutter, he proved to be an able student. He flew through his 11+ exams (UK test to stream scholastic students towards higher education), and straight to grammar school.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, unless you knew the right people, it was difficult to secure a placement at a UK university. They were fully to capacity with ex-servicemen who had been denied tertiary education during the war.

In 1950, at the age of sixteen, rather than university, Eric went to a forestry job.

Two years later, he had to front-up for two years of compulsory national service. He chose the army and was posted to Germany.

Having fulfilled that obligation, in 1954, he enrolled for a two- year course of study at a forester training school.

Britain was then, and still is, riven with class consciousness, as illustrated by a conversation he overhead during a group visit to a forestry estate. Come lunch time; while walking back to the manor, he heard the owner say: “How are we going to separate the goats from the sheep”.

Eric’s stutter came and went, depending on how confident he felt. Being lorded over by forestry owners with inherited wealth, is just the sort of situation where it would spiral and put him at a disadvantage. He started thinking about emigrating.

Before entering the training school, Eric bought a 197cc James motorbike. This was to become his conveyance to a new life in a new country.

He considered emigrating to Rhodesia, Kenya, South Africa, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. In his estimation, the first two were too politically volatile. South Africa too unjust, Australia too hot, and Canada too cold; but New Zealand was just right.

There was already a well-trodden path to settlement in New Zealand. Both New Zealand and Australia

subsidised UK citizens to travel to, and settle in, their countries. All that was required of the intending immigrant was a £10 contribution towards their ocean passage. Hence the term ‘Ten Pound Pom’.

But Eric, rather than joining the ranks of those taking an assisted passage, decided he would undertake the deeply solitary, more expensive, risky, and slower option of riding to the other side of the earth on his motorbike.

Of course he couldn’t travel the whole distance on land. He would have to cross the English Channel, the Indian Ocean separating Australia from Asia, and the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand.

Travel through France, Belgium, Germany and Austria was nearly bureaucracy free. On entering the last two, they didn’t even stamp his passport.

This changed dramatically upon entering the realm of Soviet influence.

Eric turned up in Yugoslavia just as a Soviet crack-down was about to occur in neighbouring Hungary. Soviet overlords sought to suppress a revolt, and their heavy hands reached across the border. To stay at the official camping ground in Sarajevo, Eric had to fill in a large form and pay 3/6d (the equivalent of approximately $3.50 today).

He resolved that for the remainder of his time in Yugoslavia; he would find a remote spots for overnight camping. That would be a mistake. While packing up after what was intended to be his last night before crossing into Greece, a policeman on a bicycle turned up and asked for Eric’s passport. He was then ordered to follow the officer (riding his push bike) for what became a ten-kilometres trek along a rutted road to a village.

Communicating in German, of which Eric had some grasp, he learnt that it was forbidden to camp in unauthorised areas. Eric apologised and asked for his passport back. This was denied, and he was instructed to follow the officer who, this time, travelled in the sidecar of a motor bike. The driver gunned the motor, and accelerated away, purposefully running over a dog. Both the driver and the officer looked back and laughed.

For twenty-four kilometres, Eric ate their dust until they reached a larger village. There, Eric was officially charged, fined £2 plus a further 3/- , or all up in today’s terms, about twenty-three dollars.

It was a relief to cross the border into Greece, with its sealed roads, rather than rutted tracks.

Within weeks, Yugoslavia was to be flooded by refugees fleeing Soviet repression in Hungary. If Erics experience of Yugoslav hospitality was anything to go by, the refugees would not receive a warm welcome.

Eric continued on his way, crossing Greece to Turkey, making for Istanbul where upon crossing the Bosphorus Strait he will have left Europe and entered Asia. There would be a further 1,700-kilometre westward trek through Turkey to Iran, then 2,000 Kilometres across Iran to Afghanistan.

Close to the Afghan border he encountered a 1935 London Taxi plus four Australians and two Kiwis on their way home. Travelling in convoy with them, Eric crossed Afghanistan and as far as Lahore in Pakistan; a distance of 1,400 kilometres. There, the owner of a villa under constructions, said Eric could shelter in the unfinished building. His companions, keen to be home for Christmas, pressed on.

It was now early November 1956. Pakistan was not a comfortable place to be British. Egypt had closed the Suez Canal, precipitating a military response by Britain, France and Israel. Escalation, and the spread of war was imminent, and Pakistan’s sympathies lay with their Moslem brothers in Egypt.

Eric ventured from the villa to have a look at the town. In Lahore, he encountered a crowd of dispersing demonstrators. He was booed, and hissed, and a stick whistled past him. Luckily, he was able to accelerate away from the angry mob. The next morning, he crossed into India, which although it had recently gained independence from Britain, was still an ally, and was still part of the British Commonwealth.

Motorcycle repairs and maintenance, unexpected hospitality, the sights and sensations of India, plus 1,800 kilometres of riding southeast from the Pakistan border to Calcutta, consumed the month of November.

Bound for the islands and peninsulas of Southeast Asia, Calcutta was to be his departure point from India, but he encountered a problem booking a passage. There was only one berth available on the ship he hoped to catch to Penang, in Malaysia. It was in a double cabin, and the other berth was taken by an Indian man. It was the shipping companies’ policy not to allow whites and Indians to share cabins. The problem was resolved by a bit of bending of the rules, and both Eric and the Indian man saying that they were happy to share.

India had provided a feast for Eric’s enquiring mind, but he was pleased to be leaving behind it’s poverty and filth.

On the five-day ocean passage to Penang, Eric ventured to most parts of the ship including the bridge and wireless room. He was shown how to use a sextant to shoot the sun and establish the ship’s location. The only place he didn’t go was the engine room. Nor did he want to. Even at its door, it was like a blast furnace.

After three months of not a drop of precipitation, as his ship steamed south, warm rain and humidity became the new norm

Upon disembarking at Penang, he set off for Singapore, at the tip of the Malaysian peninsula. For twenty- five meters both sides of the road the vegetation had been cleared. This was to deny cover for ambushing communist insurgents. The Malaysian forests were home to rebels seeking to overthrow the government. Britain was relinquishing her grip on Malaysia but continued striving to prevent the territory from falling under communist control.

Assisted by Australia, New Zealand and few other commonwealth countries, Britain was able to hold the line against the rebels.

At Singapore, Eric caught a ship to Fremantle. Sydney was to be his final departure point in his journey to New Zealand, but before then he wanted to explore Southern Australia, including Tasmania.

He set off to see the forests of giant Karri and Jarrah which grow in Australia’s South-West. From there, it was 1,750 kilometres eastward across the unsealed, badly corrugated Nullarbor Plains to reach a town called Ceduna.

Thirty kilometres after leaving behind the tar seal, Eric stopped for a rest, and discovered that his coat, shoes and gaiters had disappeared from atop his suitcase. He set off, retracing his tracks, and found them in the dust, twenty kilometres back.

Later that day, the bikes steering became haphazard. On inspection Eric discovered that a crack had developed in one of its front forks. There was nothing for it, but to gingerly nurse it back to Norsewood, where, he found someone to apply weld to the crack. Eric was assured that no bracing would be required.

It was late afternoon before Eric set off again, and he travelled eighty kilometres before calling it a day.

Just a few minutes after setting out the second day, the welded fork broke completely. Now, the steering was really compromised with the wheel veering up to twenty degrees from true, and, of course, presenting the ever-present threat that the other fork would break.

This time, rather than backtracking, Eric decided to press on, 130 kilometres to the next settlement. Three times he got thrown, but finally made it, and was able to find someone able to reweld the broken fork, and weld on reinforcing. It wasn’t beautiful but did the job for 1620 kilometres over a road consisting of huge potholes, sand and corrugations.

At Ceduna, Eric found a craftsman who did beautiful work welding carrier brackets etc. that were starting to fail.

He then rode 850 kilometres to Adelaide, where he had the extraordinarily good fortune of meeting an engineer who repaired crashed motor bikes. As Eric’s journey was such good advertising for the James brand, the local agents agreed to supply parts at half price. The engineer repaired or renewed the questionable parts of the bike, and a week later, Eric was cruising down the highway to Melbourne. From there he caught a ship to Tasmania.

Tasmania was a delight to Eric, though it was there that his bike became ill with dreaded ‘Big End Knock’. Unlike previous motorbike issues, all of which were remedied by a skilled welder, Big End Knock would require open heart surgery. Eric’s funds were hovering close to empty. He decided that he would do the work, himself. Although there wasn’t a James Motorcycle agent in Hobart, he was able to secure the necessary spare parts, and the use of a workshop. He then plunged into, what became, a ten-hour operation.

After crossing back to Melbourne, he rode to Canberra, then continued on his way to Sydney.

Before boarding a ship to New Zealand, he had hoped to travel north, to Brisbane, but due to his depleted funds, thought better of that. Also, the rainy season had started up north.

Instead, he spent some days touring close to Sydney, spending one fitful night sleeping in a doorway adjacent to the Sydney Harbour Bridge, as trams rattled overhead.

Sydney Harbour Bridge 1957

Eric prepared meticulously. He would be striking off into the unknown and he had to be sure that he had everything he or his bike could need. Attention to detail now, would be the difference between success or failure.

He designed, and had built, light-weight aluminium side carriers which sat either side of his rear wheel. Atop these he mounted a canvas suitcase.

Not only did he need to pack tools, a tent, a sleeping bag, food, and cooking utensils, but also visas for most of the dozen countries he would be crossing.

He wanted his journey to include travel by land, sea and air. The first two were unavoidable, while travel by air was not strictly necessary. It was simply something he wanted to tick off a list. The easiest, and least expensive way to achieve that was to catch a plane over the English Channel. On the day of his departure in September 1956 He bid farewell to his parents, rode south to Southend, where he and his bike were due, the next morning, to catch a Bristol Freighter, for a twenty-minute flight to Calais, France.

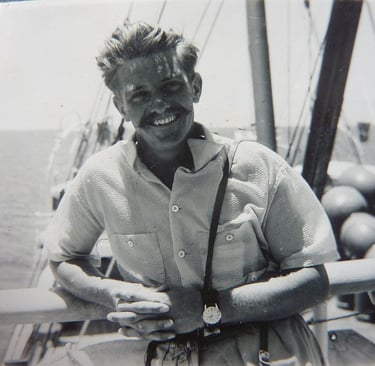

Eric Appleton, moments before setting off on his journey to New Zealand

Bristol Freighter pre-departure for Calais

London taxi crossing a ford in Afghanistan

Shipboard between Singapore and Fremantle

END PART ONE. PART TWO TO FOLLOW.

'CREATING A LEGACY IN NEW ZEALAND'